Born on the prairies of South Dakota, the Mighty Thomas Carnival has grown to become one of the finest midways in North America and has put on quality shows across the Midwest, the South, the Western States and Canada since 1928. It has a proud family lineage that has seen four generations of ownership with a fifth generation on the road in 2013. . It has also produced four Showmen’s League of America presidents: Bernard Thomas in 1977, Tom Atkins in 1987, John Hanschen in 1999, and congratulations to the newest, Chris Atkins in 2013.

Carnival founder Art B. Thomas was the youngest son of Herman and Grace Thoms, immigrants from Germany and Holland. Arriving in America during the late 1800s, the Thoms family homesteaded two farms in Iowa and North Dakota. These were not successful, perhaps owing to Art and his two brothers’ lack of interest in farming life. As a young man Art served as a fireman on the railroad, while his brother Walt was an auto body repairman, and his oldest brother Vern worked as a mechanic. Around that time Art met Axel Ben Dixon, who travelled the area with a Merry-go-round. Art invested in a Town Pump concession and accompanied Dixon from town to town selling ice-cold lemonade. In 1928 he borrowed $500 from Walt for a down payment on a No. 5 Eli Bridge Ferris Wheel, and in 1929 he purchased a Parker Carousel. He decided to change his name from Thoms to Thomas, as the phonetics was more appealing for his new enterprise: the Art B. Thomas Shows.

Making his winter quarters in Lennox, South Dakota, Art started off on a season that lasted from May to September, each spot lasting one or two days. By 1930 he decided to split the show into two units, running one himself, and his wife Ann running the other. Over time, as the carnival became renowned for its fast jumps, one unit was designated “Zephyr” and the other “Bombshell.” Vern joined his brother in 1930 as the show’s mechanic. He brought along his wife Florence, and their children, Bernard and Doris. Bernard, who was 7 years old when he joined the carnival, enjoyed the experience. He recounts those first early years:

“My sister and I traveled with our parents in a 1926 Buick. My Dad had arranged the car so that he and my Mother slept on the floor and he made a shelf for my sister and I to sleep above them. He built a large trunk on the back that contained a gas stove, pots, pans, dishes and eating utensils. We never went to a restaurant. The next season, my sister and I slept in one of the merry-go-round trucks, which also housed one of the gasoline powered electric generators. Our bed consisted of the two chariots and a mattress. My father finally built a home-made trailer house that sufficed for a couple of seasons.”

In spite of the Great Depression, Art made good on his slogan of “Bigger and better than ever,” adding a free stage show with two daily performances in in 1936. Billed to the show’s sponsors as a “thank you” to the customers, the performances drew large crowds and became as important a part of the operation as the rides and concessions during that era. Art’s wife Ann, possessing an acumen for selecting entertainment for the public, played a large role in the success of the outdoor shows. They were acclaimed “the finest north of the Dixie line and west of the Mississippi river,” and included such acts as the Cycling Kirks, the Flying Wizards, the Toyama Japanese Troupe, swing musicians Freddy and Gale LaRue, and many more. Art’s step-son-in-law William Morton, in addition to his role as the show’s publicist, had by this time risen to prominence as a nationally known magician. He and his wife Pauline travelled with the show performing as the Magical Mortons or the Great Mortoni. Some of the entertainment, such as the girl shows, would seem peculiar by today’s standards. Throughout the 30s and early 40s, a significant amount of publicity was devoted to Art’s electric Hammond Organ show. Organist Dusty Rhodes helmed the instrument, instilling “thrilling, breath-taking subtleties, extra-ordinary climaxes and melodious tone crescendos, in fields of classical, modern or popular music, with an ease and brilliance of effect never before attained.” The performance drew in musically inclined citizens from a “vast radius.” Another odd show featured crime victim and former gang member Helen Seller, who was advertised in the Register-Tribune of Akron, Iowa:

ENGAGED WITH ART B. THOMAS BOMBSHELL OF 1937

Helen Seller, who after an uncanny escape from death in the “bomb prison” devised for her and her ex-lover, lived to give South Dakota officials the clues which led them to a notorious gang of jewel robbers. Harold Baker was blown to bits in this blast of 10,000 pounds of gunpowder and 3,000 pounds of dynamite explosion, while Helen Seller crawled to safety after being slugged with hammer and shot eight times.

Helen Seller has been engaged with the Art B. Thomas Bombshell of 1937 for the remainder of the season, and in her own words you will have the opportunity to hear the story of one of the weirdest tragedies ever to befall a human being without resulting in immediate death.

Don’t fail to see and hear Helen Seller when the Show appears here.

Throughout the 30s Art steadily accumulated new rides, such as the Tilt-A-Whirl, the Loop-O-Plane, the Octopus, a Shetland pony ride, and various kiddie rides. By 1941 the fleet had grown to almost 40 trucks, and up to 160 people traveled with the show. A specially built long cookhouse truck provided employee meals free of charge, a service that was maintained until 1945. The carnival continued to flourish during the War years, benefiting from a rise in disposable income across the states, as well as a government policy that provided carnivals with rations of fuel and tires. The show’s lion, Boots, didn’t fare as well during the war. Although they tried to feed him as best they could, meat was heavily rationed and he couldn’t get near the 40 pounds or so a day that he needed. He attacked one of the workers and had to be shot. Pauline Morton kept Boots, now in the form of a rug with fully taxidermed head.

Bernard Thomas had by 1941 graduated from the pony ride to managing the show’s arcade, handling all sorts of odd jobs along the way. Around this time he found his sweetheart, Marvis Smith, Art’s step daughter by his second wife Carrie. Bernard was drafted in March of 1943, and married Marvis in early 1944 in Kentucky. Shortly thereafter he was sent to the European theater.

“May 1944 shipped overseas to Liverpool, England via Fort Dix, New Jersey. Liberty ship, 12 hours in bunk and 12 hours on deck. Lived on Tootsie Rolls, tried a meal, long lines, standing at a narrow table, etc. Soldier across from me threw up in his mess kit. I just folded mine and went back to my Tootsie Rolls. I still like them. But they still remind me of that episode.”

Bernard was assigned to the 893rd Tank Destroyer Battalion as a tank driver, landing on Omaha Beach in Normandy on June 30th. He attributed his placement to his knowledge of trucks and the firing order of six-cylinder engines, which he picked up on the carnival. They broke through at Saint-Lô on July 26th, a city so obliterated that Bernard recalled nothing standing higher than his tank. He continued fighting across France, driving an M-10 Tank Destroyer, taking the high ground overlooking Paris as the Free French liberated the city. This was about the same time that his first daughter Deanna was born in Fergus Falls, Minnesota. His battalion participated in the Parisian victory parade through the Champs-Élysées, where they were welcomed as heroes, and spend about a week in the city seeing the sights. From there he continued towards Germany under continuous front-line combat, usually parking his tank behind a house at night to sleep, then fighting again in the morning. He met with fierce fighting in the Huertgen Forest attached to the 28th Infantry Division, which was almost completely destroyed, survived the Battle of the Bulge, and went on to help capture the Remagen bridge. All told he had taken part in five battle campaigns without a scratch.

Bernard returned from Germany in September of 1945 and was discharged from the army in October. He attended his first Showmen’s League of America convention the same year. In 1946, around the time his second daughter Margaret was born, he operated a Bingo game on Art’s show. By 1947 he had purchased an interest in one unit of the carnival and managed it in partnership with Art. He took over booking duties, a part of the job that Art did not enjoy. After 1947 Art decided to retire from active management, leaving Bernard in charge of the main unit. Bernard purchased the Art B. Thomas Shows in 1951 for $100,000, the same year his third daughter Carolyn was born, and immediately launched an aggressive campaign to expand the carnival. During the 1950s he purchased a good number of new rides, including the Dodgem, the Rock-O-Plane, the Roundup, an Allan Herschell Merry-Go-Round, new Ferris Wheels, a new Octopus, a roller coaster and more. By the end of the 1950s the Thomas Shows boasted around 30 rides and a dozen or so shows. It was also booking larger events than it had before. One was the South Dakota State Fair in Huron, which Bernard first booked in 1955 and continued to serve consecutively for several decades. Others included the Colorado State Fair in Boulder, The Clay County Fair in Spencer, Iowa, the Sioux Empire Fair in Sioux Falls, as well as twelve fairs with the Western Canada Fairs Association in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba. One part of the carnival that was scaled back during this decade was the free shows. With the rise in income in America at the time, as well as a greater ability for people to travel and the appearance of television entertainment, these shows became less of a draw. The 1956 season was the last to carry large free stage shows.

The carnival continued its aggressive expansion in the 1960s. In 1962 it contracted with Canada’s Prairie Fairs Association which included Swift Current, Medicine Hat, Moose Jaw and Lethbridge. It also picked up the Canadian Lakehead Exhibition in Thunder Bay. In 1967 Bernard made a bold investment of $300,000 (over $2 million today) in new equipment, including what he considered his first “spectacular” ride, an Allan Herschell Skywheel, of which he was very proud. By this time Bernard, an aviation enthusiast, was making jumps and business trips in his private airplane, earning his nickname “the Flying Showman.” The show continued to have a strong family character. For Marvis, this was the only life she knew or cared to know, having joined the carnival around the age of 10 when her mother married Art. Bernard admitted “She does everything. From bookkeeper, office manager and actually serves as the top boss more than I do.” Their three daughters were started in the ticket box at the age of 10, growing up to fill various positions within the company. Art, although weary of life on the road at the time of his retirement, came back to run a concession. “When the carnival business gets in your blood” he said, “you don’t rinse it out overnight. So I’ve kept a finger in the pie, travel with the show, but except when called upon for advice, the operation is entirely Bernard’s.”

Bernard was equally aggressive in adding a new generation of sons in law to the company’s workforce. Deanna’s husband Ross Payne served as foreman of the new Skywheel, maintenance supervisor and fleet manager. Margaret’s husband Tom Atkins would eventually become general manager, and Carolyn’s husband John Hanschen would go on to become business manager. Carolyn recalls John’s introduction to the business in 1976:

We met when we were first pretty newly out of college, and we were both insurance underwriters. I was a multi-lines underwriter and John was a general liability underwriter for the St. Paul Insurance Company, so when we started dating John had no idea what he was getting himself into with the roots in the carnival business. So we had been dating for a while and living in Philadelphia and working in the insurance business in 1976. Then my dad asked us to go out to look at some carnival concessions that he was thinking about buying. Some water race and skeeball games. So we went down to the Atlantic City boardwalk and checked out the water race game, manufactured by International Exhibits I think. It was a balloon water race game and a monkey water race game.

Then Philadelphia Toboggan Company manufactured a skeeball game in Ashbury Park, New Jersey, so we checked those out as well. And the original idea was that we were checking those out for dad who was thinking about purchasing them, but his real intent was that we would buy them. And eventually things fell into place and that’s what happened. We got a loan from a small business association and purchased two water race games and a skeeball game in 1976. So John, without any background in the carnival business or any knowledge about what he was really getting himself into, left Philadelphia in May of 1976 and set off to Nebraska with a balloon water race game and a monkey water race game. We’re each driving along and that was John’s first ever attempt at driving a truck, and I had driven a trailer before, but we were driving straight trucks and concession trailers and made the 1800 mile trek across the country to La Vista, Nebraska to start our adventure in the carnival business. As we made our way across the country – John was a numbers guy, always has been, and he was putting pencil to paper to make sure that had made a good investment. So we started calculating that with two water races at 50 cents apiece we had 40 potential racers at any given moment, and in one water race we had a 20 second race with a 25 second recovery for the pumps to recover, but the monkey water race was faster with a 15 second race and about a 10 second recovery. So he was figuring that with even a really conservative estimate we would probably gross $1500 per game per day, which is about $3000 per day and we were gonna have these things paid off in about a month, so things were looking pretty rosy until we opened in La Vista the first night and grossed $12.50 and had to revise the business plan.

But as a greenhorn in the business, the other concessionaires were of course very helpful to John as he broke into the business. I can remember some of the guys that had been with the show for years helping him get the joints on location and convincing him that he didn’t want – you know the games were a little bit unlevel- so it would be a bad idea to try to block up the wheels on the front side of the game because that might make the counters too high, so they suggested that he dig out from under the wheels on the back side of the games. So he spent a good many hours jacking up the trailer and (laughs) digging holes under the wheels on the back side of the trailers to level them. So that was some of the help that was given as he broke into the business. But we spent a good number of years running the games and had a good time doing it. And John’s family, even though they’d never really had much of a background or source of history with the carnival business, were accepting and supportive of the work that their son had gotten into. His grandmother, one of her concerns was that she’d never seen our operation, but heard that we ran the monkey race and the water race games, and her concern every time that she saw us was “What do you do with the monkeys in the wintertime?”

In 1977 the carnival’s winter quarters was moved from Lennox, South Dakota to Austin, Texas due to the expansion of Southern portions of the route. It allowed for a longer operating season and snow-free maintenance time. Bernard hoped at first to buy a property with a private airfield to use as the winter quarters, but that didn’t work out. He finally found a good property in a convenient location. The only problem, the seller informed him, was that it used to have a trailer park on it, so there were concrete slabs throughout the property with full RV connections.

Although both Art and Bernard prided themselves on running a clean and family oriented show from the beginning, by the 1970s that definition was becoming more austere. Girl shows, crooked games and deceptive sideshows were phased out, and greater emphasis was placed on a clean and uniformed presentation of employees. Spectacular rides, such as the Enterprise, the Super Himalaya, the Flying Bobs, the Zipper and the Hurricane became the central focus. This is due in part to changes in public demand and expectation, and also to the fact that Bernard’s grandchildren were beginning to populate the midway. The first, Dawn, was born to Ross and Deanna in 1966, followed by Lisa in 1970. Tom and Margaret had Alison in 1972 and Chris in 1973. John and Carolyn had Andrew in 1980, Katherine in 1982, and Mike in 1985. The strong values of the carnival and its management attracted many long-term employees, such as Raymond Boyle, nicknamed “Chief.” Three-quarters Cherokee and a former motorcycle gang member with no family of his own, he met up with the show in Lincoln, Nebraska and decided it would be a good idea to join up with it “for good.” Chief was a passenger in Bernard’s Beechcraft Bonanza when it ejected a rod straight through the fuselage and crash landed on Interstate 90 near Mitchell, South Dakota. After climbing out of the airplane, without injury, Bernard asked Chief whether the incident had frightened him. Chief responded that because of his experience with Bernard’s trucks, with the billowing smoke, spouting oil, tremendous vibrations and horrible noise, no, in fact he was quite used to it. Chief considered the Thomas Shows to be his home and family, and he worked as foreman of the Merry-Go-Round, which he loved, until his death. Today, in his honor, a horse bears his name and likeness on the very same carousel that the Thomas Shows purchased back in 1959.

On New Year’s Day 1986, Bernard sold the Thomas Carnival to sons in law John Hanschen and Tom Atkins. They made a good team. Tom, a former Army Ranger and Vietnam veteran, boasted that his degree in Zoology gave him an edge in controlling the midway. His focus was general operations outside the office. John, with his degree in Economics from Macalester University, took care of the business from inside the office. Of course their duties overlapped considerably, due to the splitting of the show into units, as well as the reality of their shared responsibility. Margaret ran a portion of the food concessions as well as a few games, while Carolyn worked in the office and produced art and sign work. Tom’s brother Paul provided concessions and some rides. Bernard retired to his home in Austin, Texas, where he proceeded to hit two holes in one.

By 1990 around 40 carny kids from 30 employee families traveled with the carnival. It was a baby boom for the carnival unlike any other in recent memory. Melissa Mathers-Fry was one of them. She sums up the experience

“Growing up in the 90s as a kid on the carnival was a unique experience. Here you had a whole tribe of children from toddlers to late-teens traveling with their parents across country, having the carnival as their backyard playground. But at the same time instilling a strong work-ethic in them. Most of the carny kids stuck together and have a tight bond. Only other carny kids can really appreciate the experience of growing up in the business, and how it influenced them as adults.”

By the late 1990s the costs associated with crossing the border had become untenable, and with regret John and Tom decided to pull back from the Canadian circuit. They picked up some good spots in Montana to fill the void, but everyone who was present at that time still looks back fondly on the Canadian fairs. Today, in John’s estimation, the most notable thing to say about the Thomas Carnival is that it’s still the same as it always has been, after 85 years of continuous operation. And this is in spite of the modern problems that face all traveling carnivals, like the rising costs of fuel, taxes, regulation and insurance. It can offer up to 50 rides, 50 games, and 15 food concessions, serving festivals large and small across the States. It is proud to serve great fairs like the MontanaFair in Billings, The Montana State Fair in Great Falls, the Utah State Fair in Salt Lake, the Arkansas-Oklahoma State Fair in Fort Smith, the Washington Parish Free Fair in Franklinton and many more. It has provided the midway for the Morningside Days in Sioux City for over 60 years. In addition, it is still just as much a family business as it has ever been. Mike Hanschen manages the office. Katherine with her husband Brandon Petree run a number of the concessions, and have introduced a new generation of carny kids, Mamie and Georgia. Andrew handles art and promotions, and writes articles like this one. Dawn Kingsbury (Payne) sells tickets and helps out in the office. Chris Atkins now works for Leuhrs’ Ideal Rides, who team up with the Thomas Carnival in several key spots. Tom Atkins, a hall of fame member at the Outdoor Amusement Business Association and the Rocky Mountain Association of Fairs recently entered semi-retirement, but still comes out when the show really needs help. The carnival also enjoys the loyal support of employees who have been there for decades and counting, like maintenance superintendent Dave Winkey, office worker Dianna Winkey, ride superintendents Mearlin Long and Anthony Lewis, fleet mechanic Randy Muller, controller Vince Conley, game superintendents Steve Pegg and Dennis Bossman, and many more who I am remiss not to mention.

Today the Thomas Carnival stands apart for a few reasons. One is its long route and operating season. Its season starts in February and ends in November, playing a small Christmas event in between. The other is its unsurpassed heart and concern for its employees. Long-time Dodgem foreman Jeremy Dial found this out after he left the show to pursue his dream of joining the Alaskan fishery. It didn’t work out, but one phone call was all it took for the carnival to have him booked on a flight back from the Aleutian Islands to his old position on the bumper cars. As film documentarian Angela Foster said, “From what I’ve heard, Mighty Thomas is the best carnival around. They take care of their people. If someone has a problem, their bosses take care of them any way they can. They take pride in doing a job well.”

We maintain a winter quarters in Austin, Texas, where annual maintenance is performed. A full service maintenance shop is carried on the road. The shop is stocked with tools and repair parts.

We maintain a winter quarters in Austin, Texas, where annual maintenance is performed. A full service maintenance shop is carried on the road. The shop is stocked with tools and repair parts. The Thomas Carnival was founded in 1928 by Art B. Thomas in Lennox, South Dakota. The Thomas Carnival has been owned and operated by the members of the Thomas family continuously since then. Presently there are fourth generation family members working in the business. Since 1928 the Thomas Carnival has been devoted to Art Thomas’ idea of providing clean, safe and wholesome family entertainment for its customers.

The Thomas Carnival was founded in 1928 by Art B. Thomas in Lennox, South Dakota. The Thomas Carnival has been owned and operated by the members of the Thomas family continuously since then. Presently there are fourth generation family members working in the business. Since 1928 the Thomas Carnival has been devoted to Art Thomas’ idea of providing clean, safe and wholesome family entertainment for its customers.

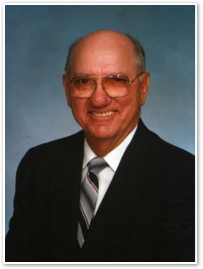

Former carnival owner Bernard P. Thomas passed away in Austin, Texas, on April 11, 2007. His Mighty Thomas Carnival has provided the midway for fairs and celebrations in 15 states and in Canada for over 50 years. He was 83.

Former carnival owner Bernard P. Thomas passed away in Austin, Texas, on April 11, 2007. His Mighty Thomas Carnival has provided the midway for fairs and celebrations in 15 states and in Canada for over 50 years. He was 83.